This is the story of how ice and ancient civilizations with

evolutionary forces have made a tropical island super-rich for wildlife on a

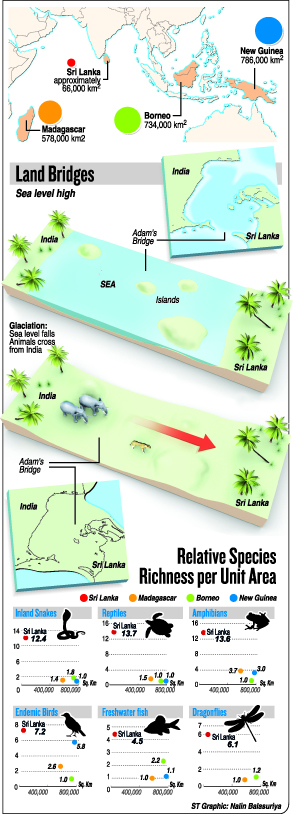

scale that is not seen anywhere on moderately or large islands. Sri Lanka’s

super-richness on a proportionate scale eclipses large islands such a

Madagascar, Borneo and New Guinea.

Alfred Russell Wallace the founder of modern biogeography

and Charles Darwin with whom he shared the theory of evolution were both

influenced by what they had observed on islands. They both would have been

surprised by Sri Lanka. Almost every key driver of evolution seems to have

played a part in shaping its biodiversity. The result is an island which is

rich in wildlife both in terms of endemic tropical biodiversity as well as

large land animals and marine mammals and in concentrations which give rise to

some of the world’s most interesting wildlife spectacles.

Alfred Russell Wallace the founder of modern biogeography

and Charles Darwin with whom he shared the theory of evolution were both

influenced by what they had observed on islands. They both would have been

surprised by Sri Lanka. Almost every key driver of evolution seems to have

played a part in shaping its biodiversity. The result is an island which is

rich in wildlife both in terms of endemic tropical biodiversity as well as

large land animals and marine mammals and in concentrations which give rise to

some of the world’s most interesting wildlife spectacles.

It’s an island which Wallace and Darwin or modern biologists

could not have imagined as so many of the bio-geographical and evolutionary

forces have come into play simultaneously, to create an unrivalled richness. To top it

all, it’s a compact country with good tourism infrastructure making it optimal

for wildlife tour operators. This article is about the physical, evolutionary,

and human factors that have made Sri Lanka something seemingly imaginary, but

yet real.

In a previous article in this newspaper (January 13, 2013) I

explained why Sri Lanka has a claim to be the best all-round wildlife

destination from a wildlife tour operator’s perspective. In this article I

explain the physical, evolutionary and human-induced forces that have made this

happen. In essence, I would simplify it conceptually into a three part

‘business model’ for the creation of a top wildlife destination. The first is a

set of physical factors, especially those influencing both surface and

underwater topography. These together with other planetary phenomena such as

plate tectonics and monsoons create structural or topographical complexity on

land and under water.

Together with time, the topographical or structural

complexity on land with monsoonal rainfall has led to the creation of distinct

climatic (and hence ecological) zones that are the engine for speciation. Sri

Lanka has benefitted from other physical factors such as an ancient Gondwana

start and having deep seas close to it unlike other continental islands.

Having set up the right conditions for evolutionary factors,

the engine of speciation needs to be fed with raw material. The output of the

species production factory will be enhanced if besides the operation of long

intervals of evolutionary time scales, new species production is boosted by

fresh stocks of mainland species through immigrant waves. Sri Lanka has managed

to produce a phenomenally above normal species richness (see box story) primarily

from evolutionary radiations within the island resulting in endemic genera and

species and later by supplementing it by land-bridging repeatedly with the

mainland. This has become more apparent recently through phylogenetic studies

using DNA. I would describe this as a five stage process for building up the

number of species.

During periods of glaciations, water is deposited as ice on

land and sea levels fall forming a land bridge in the shallow seas. This is

still physically evident in the discontinuous land bridge between Mannar and

India, known as Adam’s Bridge. New waves of immigrants are imported to the

island via the land bridge and dispersed and then isolated by rising sea levels

drowning the land bridge during warming after an ice age (a post glacial). The

new arrivals are physically stressed into niches by complex structural and

physical factors of topography and climate. In essence the process is connect–

import and disperse– isolate–stress–speciate. Glaciations have been a key agent

of the island’s super-richness in allowing large land mammals to colonise and

persist in Sri Lanka. However, phylogenetic studies indicate that most of the

radiations of endemic species occurred before the land bridge connections of

the Pleistocene epoch in the Quarternary.

The third of the large scale factors is that it has

benefited from human factors or a cultural overlay. The last has two aspects.

Firstly, the decline of ancient kingdoms has resulted in great seasonal

gatherings of wild elephants and one of the best sites for Leopards. This

creates wildlife spectacles which make great viewing on wildlife safaris.

(These spectacles have also been complemented by evolutionary factors mentioned

above resulting in species radiations which are of great scientific interest

even though species such as amphibians are not high on the list of commercial

wildlife safaris). The second aspect of the cultural overlay is that the deep

respect for life makes wildlife viewing easy as man and animals co-exist with

great tolerance.

(Next week: The three factor ‘business model’ that has been

at work to create this extraordinary richness)

No comments:

Post a Comment